After nearly 50 years of public service, a local political mainstay is finally throwing in the towel without a loss on his record.

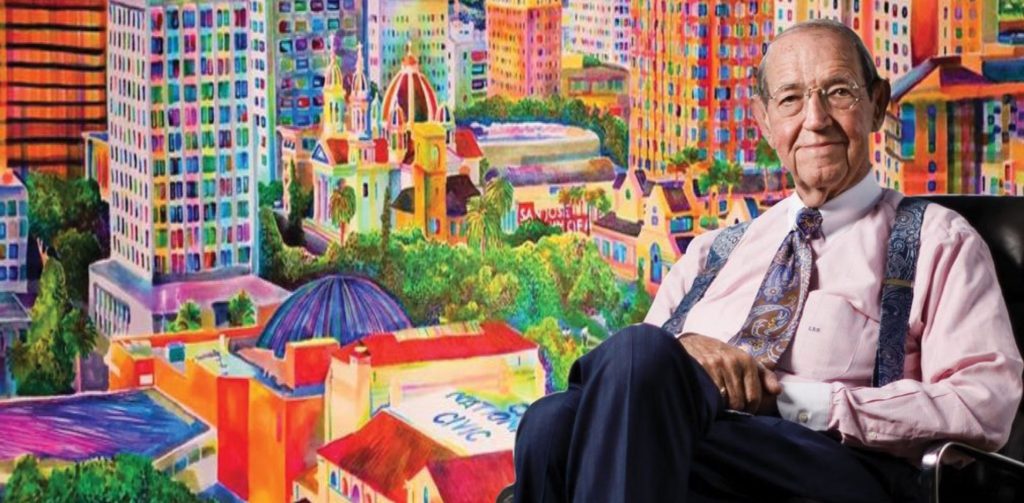

Larry Stone, Santa Clara County’s assessor, announced last month that he will not seek re-election in 2026. For the past 30 years, Stone has managed a department that determines the value of more than half a million properties — valued at roughly $700 billion — that funnel money into county coffers.

That money is the county’s largest source of discretionary spending. More than half of it goes to fund public schools and community colleges. It also goes to fund other public services, such as county hospitals, special districts like water and fire districts and paying lingering debt service from the dissolution of the state’s redevelopment agencies.

Voters have elected Stone to the position eight consecutive times, beginning in 1995. But his legacy stretches back even further, back to the mid-70s when he began serving on the Sunnyvale City Council, eventually serving two stints as the city’s mayor.

At 84, Stone is the longest-serving elected official in the county, and his tenure as assessor is the longest since 1912. He has never lost an election.

“It is time … I don’t want to go on and embarrass myself,” Stone said. “I believe I have done a good job. I am proud to leave this office as it is.”

Another reason Stone cited for his retirement is that the county finally approved an upgrade to the more-than-40-year-old software system in the assessor’s office, something he has been trying to carry out for 20 years. If that system crashed, Stone said it would be “disastrous.”

Prior to becoming the county’s tax man, the Harvard graduate had his fingers in Silicon Valley’s venture capital scene back in the 1970s.

That experience informed Stone’s ability to look at government differently, bringing an efficiency rarely seen in government. During Stone’s tenure, the office was under budget 29 out of 30 years, returning $35 million to the general fund.

Unlike other government offices — which seemingly employ more people each year, causing their budgets to balloon — Stone’s office has remained lean. In 1995, the office employed 251 people; it now has 252 employees.

When he started, he said he could feel the skepticism from employees at the assessor’s office, noting that culture change, especially in a highly unionized office, is very difficult. He brought a data-driven mindset to the office, encapsulating his motto, “what gets measured gets done.”

Now, he said, he couldn’t wrestle the performance metrics system away from employees.

“What people find is that they get rewarded for good performance, and if they don’t have good performance, we give them an opportunity to have good performance,” he said. “If someone is not producing, get rid of them. We are not about average employees. We are about above-average or excellent employees.”

Having high standards for engagement as well as creating a culture where employees thrive, instills public confidence, Stone said.

For instance, another aspect Stone said gives him pride is his effort to capture more feedback from the public and provide quality public service through surveys and streamlining access to his office.

Since that effort began, his office has regularly had a 90% or better satisfaction rating.

“Trust is a standard. It is very hard to be effective if you can’t be trusted,” Stone said. “We give people news that they don’t particularly like. I defy any government agency at any level to have metrics that show that level of approval.”

Never one to mince words, Stone has had his share of pushback from those who don’t care for his shoot-from-the-hip candor. For instance, in 2021, the Santa Clara County Democratic Central Committee denounced him, yanking its endorsement of his 2022 campaign, for remarks about his opponent the committee found “misogynistic” and “sexist.”

Stone still won that election with more than 67% of the vote.

While he acknowledges the job requires some “political moxie,” Stone also insists that the assessor’s job “has nothing to do with politics.”

That is probably a good thing, since he said the political landscape has changed since he first took office.

“I don’t see a lot of positive trends in politics these days, locally or nationally. It is a different business, if you can call politics a business. We are so polarized,” Stone said. “It used to be that you sat down with your political opponent … you could argue and get to a middle ground. Instead, [politicians nowadays] expand the open ground between them.”

To succeed as assessor, Stone said his replacement needs to have high-level management skills, “absolute integrity” and the acumen to sift through complicated assessments.

Stone said he believes Los Altos Vice Mayor Neysa Fligor, who has announced her intent to seek the seat June 26, has those qualities. She has previously worked for Stone’s office, litigating complex assessment challenges and helped secure a vendor for the new computer system.

Saratoga Council Member Yan Zhao is also running for assessor.

Stone’s retirement sets up a special election Nov. 4 to fill the final year of his term. Then, in November 2026, voters will select an assessor for a four-year term. The assessor collects a $300,000 annual salary and has no term limits.

Contact David Alexander at d.todd.alexander@gmail.com

Related Posts:

2024 Santa Clara, Sunnyvale Growth Among the Highest in the County

Assessor Will Not Appeal 49ers Stadium Tax Ruling

New Offices for Santa Clara County Assessor, Clerk-Recorder

0 comments